Chase Stuart of Football Perspective drops by to collaborate on the topic of wide receiver size and the limits of applying analytics to the subject.

Matt Waldman: Stats Ministers and Their Church

I’m a fan of applying analytics to football. Those who do it best possess rigorous statistical training or are disciplined about maintaining limits with its application. Brian Burke wrote that at its core, football analytics is no different than the classic scientific method. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are some bad scientists out there, who behave more like religious zealots than statisticians. I call them Stats Ministers. They claim objectivity when their methodology and fervor is anything but.

Stats Ministers scoff at the notion that anyone would see value in a wide receiver under a specific height and weight. They love to share how an overwhelming number of receivers above that specific height and weight mark make up the highest production tiers at the history of the position, but that narrow observation doesn’t prove the broader point that among top-tier prospects, taller wide receivers fare better than shorter ones. In fact, what the Stats Ministers ignore is that a disproportionately high number of the biggest busts were above a certain height and weight, too. Having a microphone does not mean one conducted thoughtful analysis: it could also mean one has a bully pulpit where a person with less knowledge and perspective of the subject will look at the correlation and come to the conclusion that it must be so.

However, correlation isn’t causation. Questioning why anyone would like a smaller wide receiver based on larger number of top wide receivers having size is an example of pointing to faulty ‘data backed’ points. Pointing to historical data can only get you so far: it’s not that different than the reasoning that led to Warren Moon going undrafted. That’s an extreme comparison, of course, but the structure of the argument is the same: there were very few black quarterbacks who had experienced any sort of success in the NFL, so why would Moon? Sometimes you have to shift eras to see in a clear light what “correlation isn’t causation” really looks like.

It was overwhelmingly obvious that Moon could play quarterback if you watched him. But if you’re prejudiced by past history rather than open to learning what to study on the field, then it isn’t overwhelmingly obvious. Data can help define the boundaries of risk, but when those wielding the data want to eliminate the search for the exceptional they’ve gone too far. Even as we see players get taller, stronger, and faster, wide receivers under 6’2″, 210 pounds aren’t the exception.

Analytics-minded individuals employed by NFL teams — who have backgrounds in statistics – don’t follow this line of thoughts. Those with whom I spoke acknowledged that there is an effective player archetype of the small, quick receiver. They recognize the large number of size of shorter/smaller receivers who have been impact players in the NFL that make the size argument moot: Isaac Bruce, Derrick Mason, Wes Welker, Marvin Harrison, DeSean Jackson, Torry Holt, Steve Smith, Jerry Rice, Tim Brown, Antonio Brown, Pierre Garcon, Victor Cruz, and Reggie Wayne are just a small sample of players who did not match this 6-2, 210-pound requirement.

This size/weight notion and discussion of “calibration” or what I think they actually mean–reverse regression–is also a classic statistical case of overfitting. There are too many variables and complexities to the game and the position to throw up two data points like height and weight and derive a predictive model on quality talent among receivers. The only fact about big/tall receivers is that they tend to have a large catch radius. Otherwise, there is no factual basis to assume that these players have more talent and skill.

The dangerous thing about this type of thinking is that many of these “Stats Ministers” were trained using perfect data sets in the classroom and their math is reliant on “high fit” equations. When they tackle a real world environment like football they still expect these lessons to help them when it won’t. However, there are plenty of people who are reading and buying into what they’re selling. I showed my argument above to Chase Stuart and asked him to share his thoughts. Here’s his analysis:

Chase Stuart: Analysis of the Big vs. Small WR Question

We should begin by first getting a sense of the distribution of height among wide receivers in the draft. The graph below shows the number of wide receivers selected in the first two rounds of each draft from 1970 to 2013 at each height (in inches):

The distribution is somewhat like a bell curve, with the peak height being 6’1″, and the curve being slightly skewed thereafter towards shorter players (more 6’0 receivers than 6’2″, more 5’11″ receivers than 6’3″, and so on).

Now, let’s look at the number of WRs who have made three Pro Bowls since 1970:

The most common height for a wide receiver who has made three Pro Bowls since the AFL-NFL merger is 72 inches. And while Harold Jackson is the only wide receiver right at 5’10 to make the list, players at 71 and 69 inches are pretty well represented, too. I suppose it’s easy to forget smaller receivers, so here’s the list of wide receivers 6′0 or shorter with 3 pro bowls:

Mel Gray

Mark Duper

Mark Clayton

Gary Clark

Steve Smith

Wes Welker

Harold Jackson

Charlie Joiner

Cliff Branch

Lynn Swann

Steve Largent

Stanley Morgan

Henry Ellard

Anthony Carter

Anthony Miller

Paul Warfield

Drew Pearson

Wes Chandler

Irving Fryar

Tim Brown

Sterling Sharpe

Isaac Bruce

Rod Smith

Marvin Harrison

Hines Ward

Donald Driver

Torry Holt

Reggie Wayne

DeSean Jackson

Recent history

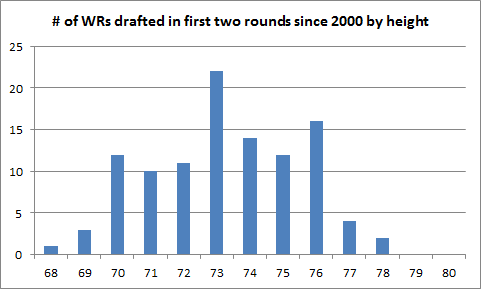

Now, let’s turn to players drafted since 2000. This next graph shows how many wide receivers were selected in the first two rounds of drafts from ’00 to ’13, based on height:

As you can see, the draft is skewing towards taller wide receivers in recent years. Part of that is because nearly all positions are getting bigger and taller (and faster), but the real question concerns whether this trend is overvaluing tall wide receivers.

It’s too early to grade receivers from the 2012 or 2013 classes, so let’s look at all receivers drafted in the first round between 2000 and 2011. There were 21 receivers drafted who were 6’3 or taller, compared to just 14 receivers drafted who stood six feet tall or shorter. On average, these taller receivers were drafted with the 13th pick in the draft, while the set of short receivers were selected, on average, with the 21st pick.

So we would expect the taller receivers to be better players, since they were drafted eight spots higher. But that wasn’t really the case. Both sets of players produced nearly identical receiving yards averages:

| Type | Rookie | Year 2 | Year 2 |

| Short | 535 | 669 | 709 |

| Tall | 567 | 676 | 720 |

Taller wide receivers have fared ever so slightly better than shorter receivers. But once you factor in draft position, that edge disappears. If you look at the ten highest drafted “short” receivers, they still were drafted later (on average, 17th overall) than the average “tall” receiver. But their three-year receiving yards line is better, reading 563-694-790. In other words, I don’t see evidence to indicate that shorter receivers, once taking draft position into account, are worse than taller receivers. If anything, the evidence points the other way, suggesting that talent evaluators are more comfortable “reaching” for a taller player who isn’t quite as good. Players like Santana Moss, Lee Evans, Percy Harvin, and Jeremy Maclin were very productive shorter picks; for some reason, it’s easy for some folks to forget the success of those shorter receivers, and also forget the failures of taller players like Charles Rogers, Mike Williams, Jonathan Baldwin, Sylvester Morris, David Terrell, Michael Jenkins, Reggie Williams, and Matt Jones.

But that’s just one way of answering the question. What I did next was run a regression using draft value using the values from my Draft Value Chart and height to predict success. If the draft was truly efficient — i.e., if height was properly being incorporated into a player’s draft position–then adding height to the regression would be useless. But if height was being improperly valued by NFL decision makers, the regression would tell us that, too.

To measure success, I used True Receiving Yards by players in their first five seasons. I jointly developed True Receiving Yards with Neil Paine (now of 538 fame), and you can read the background about it here and here.

The basic explanation is that TRY adjusts receiver numbers for era and combines receptions, receiving yards, and receiving touchdowns into one number, and adjusts for the volume of each team’s passing attack. The end result is one number that looks like receiving yards: Antonio Brown, AJ Green, Josh Gordon, Calvin Johnson, Anquan Boldin, and Demaryius Thomas all had between 1100 and 1200 TRY last year.

First, I had to isolate a sample of receivers to analyze. I decided to take 20 years of NFL drafts, looking at all players drafted between 1990 and 2009 who played in an NFL game, and their number of TRYs in their first five seasons. (Note: As will become clear at the end of this post, I have little reason to think this is an issue. But technically, I should note that I am only looking at drafted wide receivers who actually played in an NFL game. So if, for example, height is disproportionately linked to players who are drafted but fail to make it to an NFL game, that would be important to know but would be ignored in this analysis.)

To give you a sense of what type of players TRY likes, here are the top 10 leaders (in order) in True Receiving Yards accumulated during their first five seasons among players drafted between 1990 and 2009:

- Randy Moss

- Torry Holt

- Marvin Harrison

- Larry Fitzgerald

- Chad Johnson

- Calvin Johnson

- Keyshawn Johnson

- Anquan Boldin

- Herman Moore

- Andre Johnson

First, I ran a regression using Draft Pick Value as my sole input and True Receiving Yards as my output. The best-fit formula was:

TRY through five years = 348 + 131.3 * Draft Pick Value

That doesn’t mean much in the abstract, so let’s use an example. Keyshawn Johnson was the first pick in the draft, which gives him a draft value of 34.6. This formula projected Johnson to have 4,890 TRY through five years. In reality, he had 4,838. The R^2 in the regression was 0.60, which is pretty strong: It means draft pick is pretty strongly tied to wide receiver production, a sign that the market is pretty efficient.

Then I re-ran the formula using draft pick value *and* height as my inputs. As it turns out, the height variable was completely meaningless. The R^2 remained at 0.60, and the coefficient on the height variable was not close to significant (p=0.53) despite a large sample of 543 players.

In other words, NFL GMs were properly valuing height in the draft during this period.

In case you’re curious, the 15 biggest “overachievers” as far as TRY relative to draft position were, in order: Marques Colston, Santana Moss, Brandon Marshall, Darrell Jackson, Terrell Owens, Anquan Boldin, Antonio Freeman, Chad Johnson, Coles, Mike Wallace, Greg Jennings, Chris Chambers, Marvin Harrison, Hines Ward, and Steve Johnson.

In this sample, about 50% of the players were taller than 6-0, and only about 30% of the receivers were 5-11 or shorter. We shouldn’t necessarily expect to see a bunch of short overachievers, but I’m convinced that height was properly valued by NFL teams in the draft at least over this 20-year period. There may be fewer star receivers who are short, but that’s only because there are fewer star receiver prospects who are short. Once an NFL team puts a high grade on a short prospect, that’s pretty much all we need to know.

Of the 33 players drafted in the top 15, just one-third of them were six feet or shorter. As a group, there were a couple of big overachievers (Torry Holt, Lee Evans), some other players who did very well (Joey Galloway, Terry Glenn, and Donte Stallworth), and a few big busts (Desmond Howard, Ted Ginn, Troy Edwards, and Peter Warrick). Ike Hilliard and Mike Pritchard round out the group. But I see nothing to indicate that short receivers who are highly drafted do any worse than tall receivers who are highly drafted. It’s just that usually, the taller receiver is drafted earlier.

Waldman: Why the Exceptional is Valuable

Chase’s analysis echoes what I have heard from those with NFL analytics backgrounds: There are too many variables to consider with raw stats to indicate that big receivers are inherently better than small receivers and there are viable archetypes of the effective small receiver.

What concerns me about the attempts to pigeonhole player evaluation into narrower physical parameters is that if taken too far one might as well replace the word “talent” in the phrase “talent evaluation” and use “athletic” or “physical” in its place. I may be wrong, but I get the sense that some of these Stats Ministers–intentionally or otherwise–dislike the exceptional when it comes to human nature. They’re seeking a way to make scouting a plain of square holes where the square pegs fit neatly into each place.

The problem with this philosophy is that once a concept, strategy, or view becomes the “right way” it evolves into the standard convention. Once it becomes conventional, it’s considered “safe.” However this is not true in the arena of competition. If you’re seeking the conventional, you’ve limited the possibilities of finding and creating environments for the exceptional to grow.

Many players who didn’t match the ideal size for their positions and had success were difference makers on winning teams–often Super Bowl Champions. I’d argue that exceptions to the rule that succeed are often drivers of excellence:

- Russell Wilson didn’t meet the faulty “data backed” physical prototypes for quarterback and picking this exception to the rule in the third round earned them exceptional savings to acquire or keep other players for a Super Bowl run.

- Rod Smith was too short, too slow, a rookie at 25, and not even drafted. But like a lot of his peers I mentioned above, his production was a huge factor for his team becoming a contender. The fact he was the exception to the rule freed Denver to acquire other pieces to the puzzle.

- Joe Montana was too small, threw a wobbly ball, and was a third-round pick who was more of a point guard than full-fledged pocket passer, but he was just the type of player Bill Walsh was seeking in an offense that changed the entire course of the game. But at the time, the west coast offense was the exception to the rule that turned the league upside down.

- Buddy Ryan the Bears drafted a bunch of defenders that didn’t meet physical prototypes for traditional roles in a 4-3, but the 46 defense took Chicago to Super Bowl dominance.

- Drew Brees, Darren Sproles, and Marques Colston were exceptions to the rule. The Saints offense has been the driver for this team’s playoff and Super Bowl appearances.

I could name more, but the point isn’t to list every player. Why should I? Players who become top starters in the NFL are by very definition the exception to the rule. The only thing height gives a wide receiver is potential position on a target due to wing span, but it doesn’t help hand-eye coordination, body position, route running, comfort with physical contact, and understanding of a defense.

There are also smaller players with good arm length, leaping ability, quickness, and strength to earn similar, if not better position on a target. Even when the smaller receivers lack the same caliber of physical measurements as the bigger players, if they possess all of the other traits of a good receiver that these big athletes lack then size doesn’t matter.

There are legitimate archetypes for smaller, quick receivers with change of direction. However, there are social biases with these correlations that filter out players from the earliest stages of the game. These biases include the idea that the vast majority of these types of players are in the highest levels of football so anything different should be discouraged at the high school and college level–think white wide receivers, running backs, and cornerbacks as examples.

Players who succeed in defying these social biases and also possess the skill and persistence to overcome them. I’ve shown this video before, but physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson makes a strong point against “data backed” arguments of this nature when he answered a question posed about the small number of female and black scientists in the world. Harvard President Lawrence Summers hazarded a guess that it was genetics. Tyson’s answer is a great example why correlation isn’t causation.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/KEeBPSvcNZQ?start=3689]

The greatest irony about this specific crowd of data zealots is that they are often the first to complain about coaching tendencies that have same biases.

Maybe rookie receivers with the dimensions of Paul Richardson–or for that matter Jeremy Gallon or Odell Beckham–don’t become productive fantasy options or football players as often as bigger players based on correlating data. However, pointing to past history and scoffing at the wisdom of making an investment is like stating that it was a fact in the 15th century that dragons lie at the edge of the flat world we live in.

If you’re going to avoid investing in a player–or encourage others to do so–use good reasoning. Looking at the data is helpful, but the NFL isn’t a perfect data set. There are some data analysts writing about football that derive ideas reliant on a lot of highly fit equations that don’t work in a real world situation. However, they expect perfection and it’s not going to happen. They also behave as if data only tells the truth–and when that data lacks a fit, context, or proper application, it’s a little scary.

I want to see analytics succeed in the NFL, but like film study it’s not the answer. These two areas–when executed well–can contribute to the answer. However, the NFL–beyond some individual cases–hasn’t made significant advances in either area.

I suppose when you have a monopoly in the marketplace combined with a socialistic system for spreading the wealth owners don’t have significant motivation to become innovative with player evaluation. If they did, they’d be spending more money on making these processes rather than cycling through coaches and GMs every 3-5 years.

In case you’re new to the RSP blog, Chase Stuart runs the excellent blog Football Perspective. He also writes for Footballguys and Football Outsiders. I recommend you check out more of his work.